Cattle Egret

General Description

The Cattle Egret is a small heron, usually found near grazing mammals. Only half the size of a Great Egret, the Cattle Egret's size is a useful field mark. Juveniles and adults in non-breeding plumage are pure white with dark legs. Adults have yellow bills. The juvenile's bill is dark but turns yellow by its first fall. Adults in breeding plumage are unmistakable, with buff-colored plumes creating patches on the back, breast, and crest. Breeding adults also have orange bills and reddish-orange legs.

Habitat

The Cattle Egret's feeding habitat is open country, where it is most often found associated with cattle (in North America). In other countries, it is found near a variety of large grazers. Breeding habitat is similar to that of other herons and egrets, in colonies near the water, often in a swamp or on an island.

Behavior

Although a gregarious bird at all seasons, the Cattle Egret is at the edge of its range in Washington and so is usually found here alone or in small groups. Cattle Egrets follow cattle and other grazers to take advantage of the insects stirred up in their wake.

Diet

The Cattle Egret eats mainly insects, especially grasshoppers, and in some parts of the world, parasitic flies. An adaptable species, they have been known to eat nestling birds and eggs, and to scavenge in dumps.

Nesting

Cattle Egrets typically first breed at two years old. They nest in colonies with other heron and egret species. The male displays within his territory to attract a mate who then joins him on the territory. Occasionally the male has more than one female on his territory, but that is more common at the beginning of the breeding season. The pair bond lasts for the duration of the nesting season, but birds do not appear to re-pair with the same mates the following year. Once paired, the male brings nest material to the female, who builds the stick nest in a tree or shrub. Often live twigs with leaves are broken off and added to the nest. Both parents incubate the 3-4 eggs for about 24 days. Both regurgitate food for the young. Cattle Egrets are very attentive parents, and one of the parents is almost constantly with the young for the first 10 days. After about three weeks, the young start climbing around the nest, and first flight is around 4 weeks. The young become independent at about 6 ½ weeks, are strong flyers, and are able to disperse long distances.

Migration Status

Migration in the fall and spring is prolonged, lasting from February through May and September through November. Once they fledge, young birds wander long distances in random directions. The long-distance dispersal of juveniles from July through November is what typically brings Cattle Egrets to Washington, and is responsible for their impressive colonization of new areas.

Conservation Status

Although numbers throughout North America vary considerably from year to year, the Cattle Egret has experienced a long-term population increase and range expansion that seems to be tapering off in recent years. Their dispersal tendencies, gregarious nature, and adaptability have all contributed to this increase. In the 1870s and 1880s, they spread from Africa to northeastern South America. They reached Florida in the early 1940s and began to breed there in 1953. By 1964, they had reached the West Coast, and were breeding in southern California by 1979. Cattle Egrets were first recorded in Washington in 1967 but have not yet bred here. Their range expansion reached as far as Alaska in 1981. Cattle Egrets may compete with native species for nest sites in some areas, but in general, their impact on native species is considered minimal. In many areas they are considered beneficial as they may help control parasitic flies and other insect pests, improving cattle health. Their cosmopolitan nature, however, may be a health threat as they can spread disease to new areas.

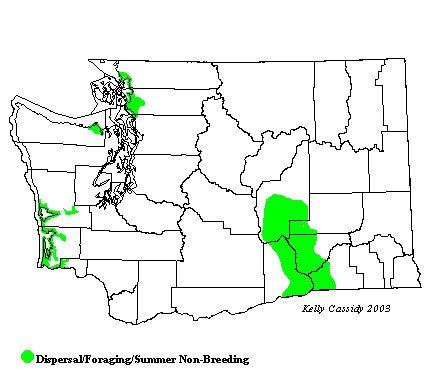

When and Where to Find in Washington

There have been only a few records of Cattle Egret's occurance in Washington during the breeding season, with records from Skagit and Pacific Counties in 1995 and Clark County in 1997. In 2002, two birds were seen at Burbank in Walla Walla County from mid-May to mid-June. There are no records of actual breeding. In the fall in most years, a few Cattle Egrets can be found on the coast of Washington, in Puget Sound, and in eastern Washington.

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | ||||||||||||

| Puget Trough | R | R | R | R | ||||||||

| North Cascades | ||||||||||||

| West Cascades | ||||||||||||

| East Cascades | ||||||||||||

| Okanogan | ||||||||||||

| Canadian Rockies | ||||||||||||

| Blue Mountains | ||||||||||||

| Columbia Plateau | R | R |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map